Three factors must be considered in the

evaluation of the dielectric capability of an insulation structures

—the voltage distribution must be calculated between different

parts of the winding, the dielectric stresses are then calculated

knowing the voltages and the geometry, and finally the actual

stresses can be compared with breakdown or design stresses to

determine the design margin.

Voltage distributions are linear when

the flux in the core is established. This occurs during all power

frequency test and operating conditions and to a great extent under

switching impulse conditions (Switching impulse waves have front

times in the order of tens to hundreds of microseconds and tails in

excess of 1000 μs.)

These conditions tend to stress the

major insulation and not inside of the winding. For shorter-duration

impulses, such as full-wave, chopped-wave, or front-wave, the voltage

does not divide linearly within the winding and must be determined by

calculation or low voltage measurement. The initial distribution is

determined by the capacitative network of the winding.

For disk and helical windings, the

capacitance to ground is usually much greater than the series

capacitance through the winding. Under impulse conditions, most of

the capacitive current flows through the capacitance to ground near

the end of the winding, creating a large voltage drop across the line

end portion of the coil.

The capacitance network for shell form

and layer-wound core form results in a more uniform initial

distribution because they use electrostatic shields on both terminals

of the coil to increase the ratio between the series and to ground

capacitances.

Static shields are commonly used in

disk windings to prevent excessive concentrations of voltages on the

line-end turns by increasing the effective series capacitance within

the coil, especially in the line end sections.

Interleaving turns and introducing

floating metal shields are two other techniques that are commonly

used to increase the series capacitance of the coil.

Following the initial period,

electrical oscillations occur within the windings. These oscillations

impose greater stresses from the middle parts of the windings to

ground for long-duration waves than for short-duration waves.

Very fast impulses, such as steep

chopped waves, impose the greatest stresses between turns and coil

portions. Note that switching impulse transient voltages are two

types— asperiodic and oscillatory. Unlike the asperiodic waves

discussed earlier, the oscillatory waves can excite winding natural

frequencies and produce stresses of concern in the internal winding

insulation.

Transformer windings that have low

natural frequencies are the most vulnerable because internal damping

is more effective at high frequencies. Dielectric stresses existing

within the insulation structure are determined using direct

calculation (for basic geometries), analog modeling, or most

recently, sophisticated finite-element computer programs.

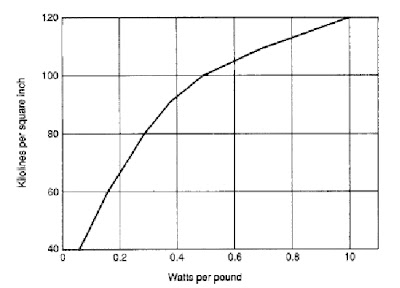

Allowable stresses are determined from

experience, model tests, or published data. For liquidinsulated

transformers, insulation strength is greatly affected by

contamination and moisture. The relatively porous and hygroscopic

paper-based insulation must be carefully dried and vacuum impregnated

with oil to remove moisture and gas to obtain the required high

dielectric strength and to resist deterioration at operating

temperatures.

Gas pockets or bubbles in the

insulation are particularly destructive to the insulation because the

gas (usually air) not only has a low dielectric constant (about 1.0),

which means that it will be stressed more highly than the other

insulation, but also air has a low dielectric strength.

High-voltage dc stresses may be imposed

on certain transformers used in terminal equipment for dc

transmission lines. Direct-current voltage applied to a composite

insulation structure divides between individual components in

proportion to the resistivities of the material.

In general the resistivity of an

insulating material is not a constant but varies over a range of

100:1 or more, depending on temperature, dryness, contamination, and

stress. Insulation design of high-voltage dc transformers in

particular require extreme care.