POWER TRANSFORMER | DISTRIBUTION TRANSFORMER | TRANSFORMER DESIGN | TRANSFORMER PRINCIPLES | TRANSFORMER THEORY | TRANSFORMER INSTALLATION | TRANSFORMER TUTORIALS

Showing posts with label Short Circuit. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Short Circuit. Show all posts

PHASE SHIFTING TRANSFORMER SHORT CIRCUIT CHARACTERISTIC

Short Circuit Requirements

General

PSTs shall comply with the short circuit requirements of IEEE Std C57.12.00-2000, unless otherwise agreed upon by the purchaser and manufacturer.

Transformer categories

The kVA rating to be considered for determining the category should be the equivalent to the rating according to IEEE Std C57.12.00-2000.

Short-circuit current magnitude

The manufacturer shall determine the most onerous conditions for short circuit on every winding or active part in accordance with IEEE Std C57.12.00-2000.

These conditions should take into account the large impedance swings that can occur as the tap position is changed from the extreme positions to the mid position.

Since the system short-circuit levels are critical to the design of PSTs, the user shall specify the maximum system short-circuit fault levels expected throughout the life of the unit.

If a short-circuit test is performed, it shall be done in accordance with IEEE Std C57.12.90-1993.

The test shall be carried out on the tap position that produces the most severe stresses in each winding. This may require more than a single test depending on the type of construction.

For two-core PSTs this usually requires a test on the zero phase-shift position, as this position involves only the series transformer, and a second test on a position to be agreed upon between customer and manufacturer.

OPEN CIRCUIT CHARACTERISTICS OF POWER TRANSFORMER BASIC INFORMATION

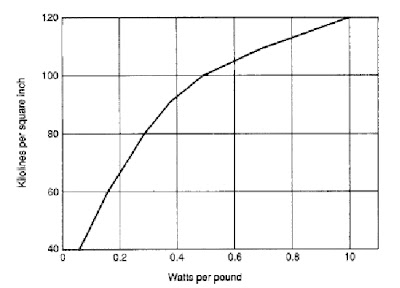

The core loss (no-load loss) of a power

transformer may be obtained from an empirical design curve of watts

per pound of core steel (Fig. below). Such curves are established by

plotting data obtained from transformers of similar construction.

The basic loss level is determined by

the grade of core steel used and is further influenced by the number

and type of joints employed in construction of the core. Figure 10-1

applies for 9-mil-thick M 3-grade steel in a single-phase core with

45” mitered joints.

Loss for the same grade of steel in a

3-phase core would usually be 5% to 10% higher. Exciting current for

a power transformer may be established from a similar empirical curve

of exciting volt-amperes per pound of core steel.

The steel grade and core construction

are the same as for Fig. 10-1. The exciting current characteristic is

influenced primarily by the number, type, and quality of the core

joints, and only secondarily by the grade of steel.

Because of the more complex joints in

the 3-phase core, the exciting volt-amperes will be approximately 50%

higher than for the single-phase core. The exciting current of a

transformer contains many harmonic components because of the greatly

varying permeability of the steel.

For most purposes, it is satisfactory

to neglect the harmonics and assume a sinusoidal exciting current of

the same effective value. This current may be regarded as composed of

a core-loss component in phase with the induced voltage (90DEG ahead

of the flux) and a magnetizing component in phase with the flux.

Sometimes it is necessary to consider

the harmonics of exciting current to avoid inductive interference

with communication circuits. The harmonic content of the exciting

current increases as the peak flux density is increased.

Performance can be predicted by

comparison with test data from previous designs using similar core

steel and similar construction. The largest harmonic component of the

exciting current is the third.

Higher-order harmonics are

progressively smaller. For balanced 3-phase transformer banks, the

third harmonic components

POWER TRANSFORMER SHORT CIRCUIT FORCES BASICS AND TUTORIALS

SHORT CIRCUIT FORCES ON POWER TRANSFORMERS BASIC INFORMATION

What Are The Short Circuit Forces Acting On Power Transformers?

Forces exist between current-carrying conductors when they are in an alternating-current field. These forces are determined using :

F = B I sin x

where

F = force on conductor

B = local leakage flux density

x = angle between the leakage flux and the load current. In transformers, sin x is almost

always equal to 1.

Thus

B = uI

and therefore

F directly proportional to I^2

Since the leakage flux field is between windings and has a rather high density, the forces under shor tcircuit conditions can be quite high. This is a special area of transformer design. Complex computer programs are needed to obtain a reasonable representation of the field in different parts of the windings.

Considerable research activity has been directed toward the study of mechanical stresses in the windings and the withstand criteria for different types of conductors and support systems.

Between any two windings in a transformer, there are three possible sets of forces:

• Radial repulsion forces due to currents flowing in opposition in the two windings

• Axial repulsion forces due to currents in opposition when the electromagnetic centers of the two windings are not aligned

• Axial compression forces in each winding due to currents flowing in the same direction in adjacent

conductors

The most onerous forces are usually radial between windings. Outer windings rarely fail from hoop stress, but inner windings can suffer from one or the other of two failure modes:

• Forced buckling, where the conductor between support sticks collapses due to inward bending into the oil-duct space

• Free buckling, where the conductors bulge outwards as well as inwards at a few specific points on the circumference of the winding

Forced buckling can be prevented by ensuring that the winding is tightly wound and is adequately supported by packing it back to the core. Free buckling can be prevented by ensuring that the winding is of sufficient mechanical strength to be self-supporting, without relying on packing back to the core.

What Are The Short Circuit Forces Acting On Power Transformers?

Forces exist between current-carrying conductors when they are in an alternating-current field. These forces are determined using :

F = B I sin x

where

F = force on conductor

B = local leakage flux density

x = angle between the leakage flux and the load current. In transformers, sin x is almost

always equal to 1.

Thus

B = uI

and therefore

F directly proportional to I^2

Since the leakage flux field is between windings and has a rather high density, the forces under shor tcircuit conditions can be quite high. This is a special area of transformer design. Complex computer programs are needed to obtain a reasonable representation of the field in different parts of the windings.

Considerable research activity has been directed toward the study of mechanical stresses in the windings and the withstand criteria for different types of conductors and support systems.

Between any two windings in a transformer, there are three possible sets of forces:

• Radial repulsion forces due to currents flowing in opposition in the two windings

• Axial repulsion forces due to currents in opposition when the electromagnetic centers of the two windings are not aligned

• Axial compression forces in each winding due to currents flowing in the same direction in adjacent

conductors

The most onerous forces are usually radial between windings. Outer windings rarely fail from hoop stress, but inner windings can suffer from one or the other of two failure modes:

• Forced buckling, where the conductor between support sticks collapses due to inward bending into the oil-duct space

• Free buckling, where the conductors bulge outwards as well as inwards at a few specific points on the circumference of the winding

Forced buckling can be prevented by ensuring that the winding is tightly wound and is adequately supported by packing it back to the core. Free buckling can be prevented by ensuring that the winding is of sufficient mechanical strength to be self-supporting, without relying on packing back to the core.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Previous Articles

-

▼

2025

(162)

-

▼

December

(39)

- MASTERING SIMULATION IN ELECTRONIC DESIGN: A COMPR...

- UNDERSTANDING THE LIMITATIONS AND POTENTIAL OF CIR...

- MASTERING OSCILLOSCOPES AND LOGIC ANALYZERS: A COM...

- MASTERING OSCILLOSCOPES: A GUIDE FOR ELECTRICAL EN...

- UNDERSTANDING MULTIMETERS AND OSCILLOSCOPES: A COM...

- MASTERING ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING: THE ESSENTIAL TO...

- UNDERSTANDING CONSTANT CURRENT SOURCES IN ELECTRON...

- INNOVATIVE CIRCUITS: ENHANCING ELECTRONIC DESIGN W...

- OPTIMIZING PRODUCT DESIGN THROUGH MODULARIZATION A...

- ENGINEERING DESIGN: ADAPTING TO CHANGE IN A DYNAMI...

- ENSURING ROBUSTNESS IN ELECTRONIC DESIGN: A COMPRE...

- DESIGNING ROBUST ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS: NAVIGATING IN...

- UNDERSTANDING COMPONENT ERRORS IN ELECTRONIC DESIGN

- UNDERSTANDING ALTERNATING CURRENT: A DEEP DIVE INT...

- UNDERSTANDING ELECTRICITY: THE SCIENCE BEHIND CURR...

- UNDERSTANDING THEVENIN'S THEOREM: A DEEP DIVE INTO...

- UNDERSTANDING THEVENIN’S THEOREM: A KEY TOOL IN CI...

- MASTERING ELECTRICAL CIRCUITS: THE POWER OF THEVEN...

- MASTERING ELECTRICAL FUNDAMENTALS: A DEEP DIVE INT...

- UNDERSTANDING TIME CONSTANTS IN ELECTRONICS: THE K...

- UNDERSTANDING VOLTAGE DIVIDERS AND RC CIRCUITS IN ...

- UNDERSTANDING ELECTRICAL IMPEDANCE: THE FOUNDATION...

- MASTERING OHM'S LAW: THE CORNERSTONE OF ELECTRICAL...

- MASTERING THE FUNDAMENTALS: WHY BASIC PRINCIPLES A...

- MASTERING THE FUNDAMENTALS: THE LEGO APPROACH TO E...

- MASTERING ELECTRONIC CIRCUITS: THE PATH TO INTUITI...

- INTUITIVE SIGNAL ANALYSIS: MASTERING THE ART OF PR...

- UNDERSTANDING OSCILLATION IN ELECTRICAL AND MECHAN...

- UNDERSTANDING ELECTRICAL COMPONENTS: A DEEP DIVE I...

- MASTERING ESTIMATION IN ENGINEERING: A CRUCIAL SKI...

- MASTERING UNIT CONVERSIONS: A CRUCIAL SKILL FOR EV...

- UNLOCKING THE MAGIC OF ELECTRICITY: A GUIDE TO UND...

- UNDERSTANDING ELECTRICITY: THE DYNAMIC FORCE BEHIN...

- UNDERSTANDING ELECTRICITY: VOLTAGE, CURRENT, AND T...

- UNDERSTANDING ELECTRICITY: A DEEP DIVE INTO CHARGE...

- UNDERSTANDING ATOMIC STRUCTURE: CHARGE AND ELECTRO...

- UNDERSTANDING ELECTRICITY: A JOURNEY THROUGH ATOMS...

- MASTERING ENGINEERING PRINCIPLES: A GUIDE FOR STUD...

- UNLOCKING THE POWER OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING: A G...

-

▼

December

(39)